NVIDIA Corporation (NVDA) has been the poster child for the AI boom, with its stock surging to a market capitalization exceeding $4.43 trillion as of August 2025. The company's Q2 FY2026 earnings, released this week, reported record Data Center revenue of $41.1 billion, a 154% year-over-year increase. However, a closer examination of the underlying fundamentals - drawn from NVDA's 10-Q filing and recent market discussions - reveals symptoms of a classic asset bubble. Overreliance on a narrow customer base, questionable capital allocation, and decelerating growth momentum suggest the stock is overinflated and vulnerable to a sharp decline.

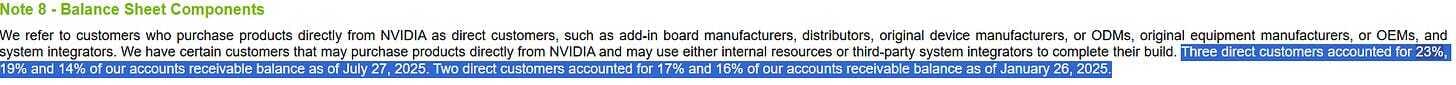

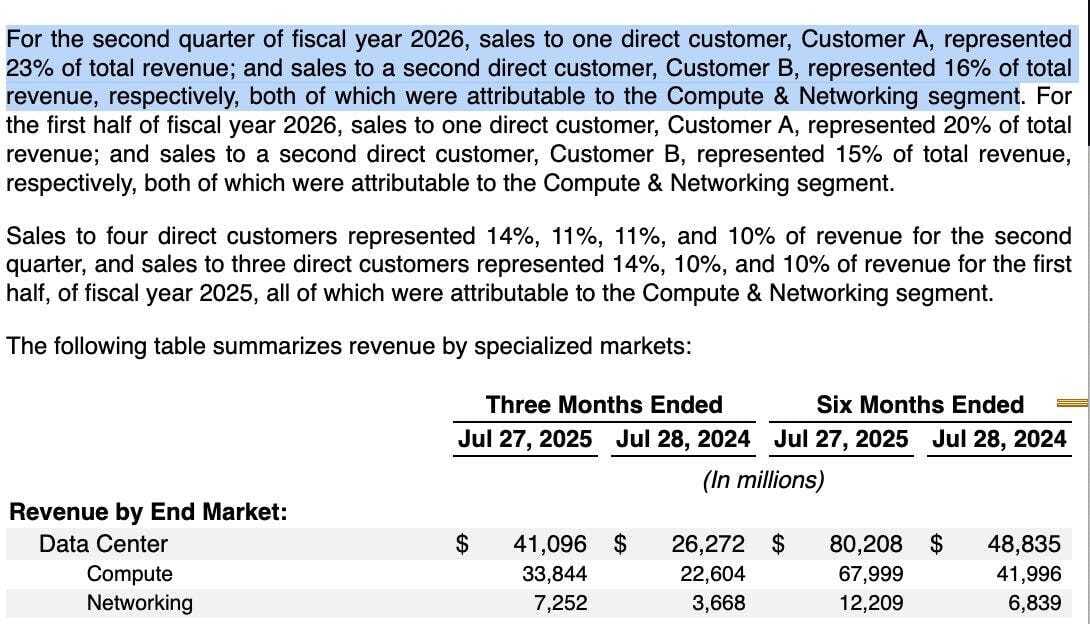

At the heart of NVDA's vulnerability is extreme customer concentration. According to the 10-Q, two direct customers accounted for 44.4% of Q2 Data Center revenue, with one contributing 23% and the other 16%.

This dependency has intensified: Accounts receivable now show three customers representing 56% (23%, 19%, and 14%), up from 33% across two in January. These buyers are likely hyperscalers like Microsoft and Meta, engaged in a capex arms race for AI infrastructure. While some argue these "direct customers" are intermediaries (e.g., assemblers like Foxconn serving thousands downstream), the risk remains acute. If even one major buyer reduces spending - due to AI ROI shortfalls or economic pressures - NVDA's revenue could plummet. Historical parallels, such as Enron's accounting scandals or Cisco's dot-com bust, underscore how concentrated revenue streams amplify fragility in high-growth tech firms.

Compounding this is supplier dependency. NVDA relies on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) for approximately 90% of its advanced chip production. Geopolitical tensions in the Taiwan Strait pose an existential threat; any disruption could halt supply chains, eroding NVDA's competitive moat. This one-two punch of customer and supplier concentration creates a precarious foundation, where external shocks could trigger cascading failures.

Geopolitical headwinds intensify: China, once 40% of revenue via H20 chips and black markets, faces bans and U.S. export stalls. Chinese firms are shifting to local alternatives like Huawei, potentially flooding markets with resold GPUs as in past mining bans. Analysts warn of guidance misses due to approvals and tariffs.

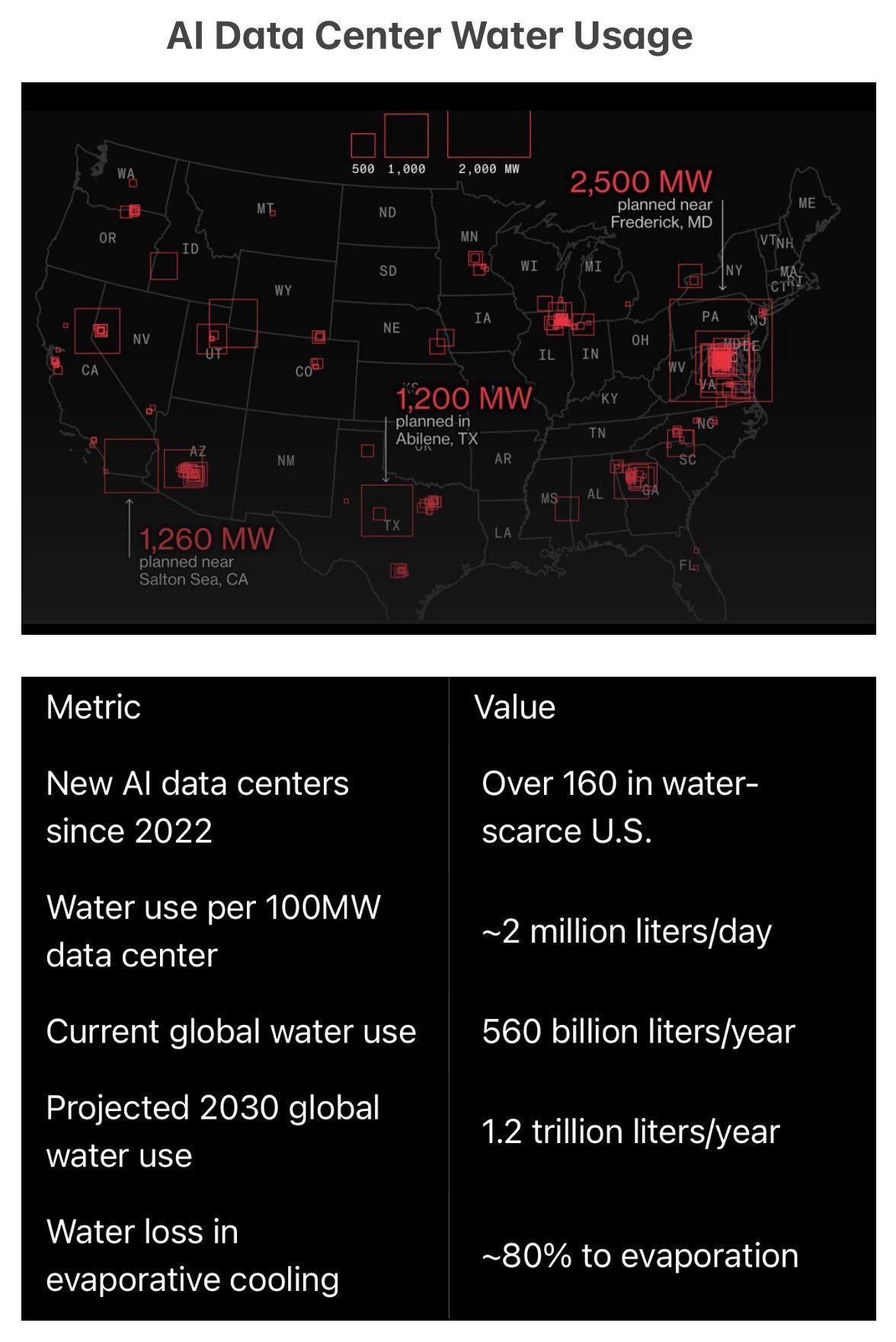

Further exacerbating these risks are infrastructure bottlenecks in the US, where electricity and water supplies are insufficient to support AI at scale. AI data centers, powered by NVIDIA's GPUs, consume vast resources: Globally, they could demand 945 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity by 2030, more than double current levels. In the US, projections show data center power needs rising to 123 gigawatts (GW) by 2035, potentially accounting for 12% of national electricity by 2028. The outdated grid lags behind, with new capacity additions four times slower than demand growth, risking blackouts and higher costs. Water usage is equally concerning: An average data center uses 300,000 gallons daily (equivalent to the usage of approximately 6,500 homes), and since 2022, over 160 new AI centers have been built in drought-prone areas like Texas and Arizona. By 2027, global consumption could reach 1.7 trillion gallons, with 80% lost to evaporation. What's behind this high demand? The real AI bottleneck? H₂O. These constraints could delay data center expansions, throttling NVIDIA's growth.

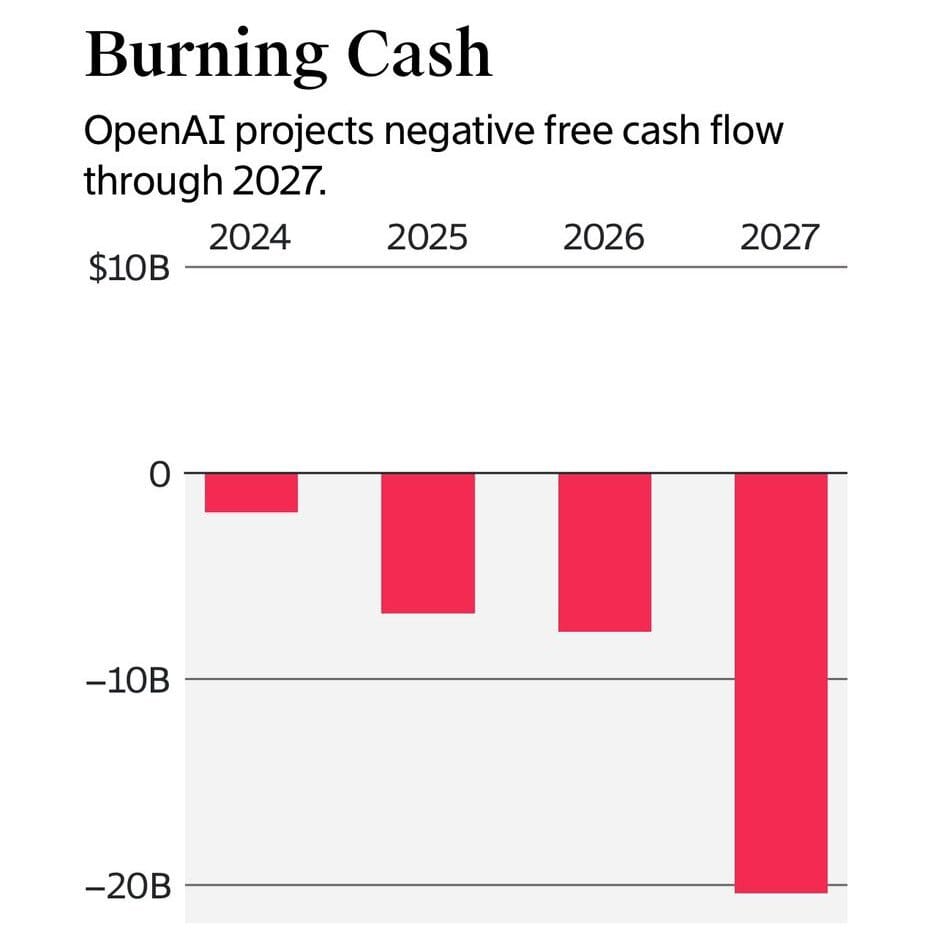

Adding to the fragility is AI's shaky economic foundation, reliant on a cascading cost structure propped up by venture capital (VC). A typical user pays $200/year for an AI app, but costs escalate: The app spends $500 on models (with $300 VC-subsidized), models cost $1,000 in compute ($500 VC-covered), and infrastructure requires $10,000 in GPUs - creating a 50x gap filled by investors. With $80 billion in VC funding in Q1 2025 alone (EY data), but firms like OpenAI burning ~$10 billion annually through 2027 - mirroring WeWork's VC-dependent downfall - and a 50:1 capex-to-revenue ratio signaling inefficiency, the model teeters. Hardware depreciation accelerates this: GPUs degrade 50% faster under AI loads (2023 IEEE study), shortening lifespans to 2-3 years, as seen in Amazon's $920 million write-off and Meta's potential $5 billion hit in 2026. Consumer resistance compounds it - willingness to pay drops 30% for disclosed AI content (BSI 2025 study) - leaving price hikes or cost cuts as uncertain fixes. If VC pulls back, AI demand for NVDA's chips could evaporate.

This unsustainable model is exemplified by Microsoft's (MSFT) partnership with OpenAI, where MSFT earns AI revenues by effectively "selling" Azure cloud credits to OpenAI, which in turn burns billions annually in losses. Described as "vendor financing on steroids," MSFT has invested over $13 billion in OpenAI, much of it in Azure credits rather than cash (e.g., $10 billion in credits and only $1 billion cash in one round). OpenAI uses these credits to run its operations on Azure, generating booked revenue for MSFT's cloud segment - contributing to Azure's 33% growth, with AI services adding 12 percentage points. However, OpenAI's losses are staggering: $5-8 billion in 2024, projected to escalate to $14 billion by 2026 and $44 billion cumulative through 2028, despite $10 billion in annual recurring revenue. In essence, MSFT indirectly funds OpenAI's deficits while recognizing income from the credits, inflating AI ecosystem figures and sustaining demand for NVDA GPUs in a self-reinforcing loop. MSFT takes a 20-75% cut of OpenAI profits until recouping investments, but with OpenAI's burn rate, this resembles aggressive accounting that masks underlying inefficiencies. If OpenAI's losses persist or partnerships shift (e.g., OpenAI seeking rival clouds), this could unravel, reducing compute demand and hitting NVDA hard.

Capital allocation further exposes short-term priorities over long-term innovation. Over the past six months, NVDA expended $23.8 billion on share buybacks - more than double the $11.3 billion combined on R&D ($8.2 billion) and equipment/software ($3.1 billion). While buybacks boost earnings per share and support stock prices, they signal skepticism about reinvesting in AI's purported transformative potential. If management truly believed in sustained AGI-driven demand, why prioritize financial engineering? This approach echoes pre-2008 financial institutions, where buybacks masked underlying weaknesses until the bubble burst.

Insiders, including CEO Jensen Huang, sold billions amid hype. AI ROI disappoints - 95% of firms see no returns, signaling diminishing gains and commoditization.

Competition rises: AMD, ASICs, and inference chips erode NVDA's 80% share, with antitrust scrutiny ahead.

Valuations at 50x forward earnings assume endless growth, but Q3 slowdowns, overcapacity, and Ponzi-like dynamics (e.g., CoreWeave borrowing for GPUs, OpenAI burning compute, stock levitating) foreshadow collapse.

Echoing dot-com and crypto crashes, NVDA's fragility could trigger a market-wide correction.

Early investors rotate into safer assets, while retail and index funds absorb the exposure.

Investors: Diversify now.

Updates:

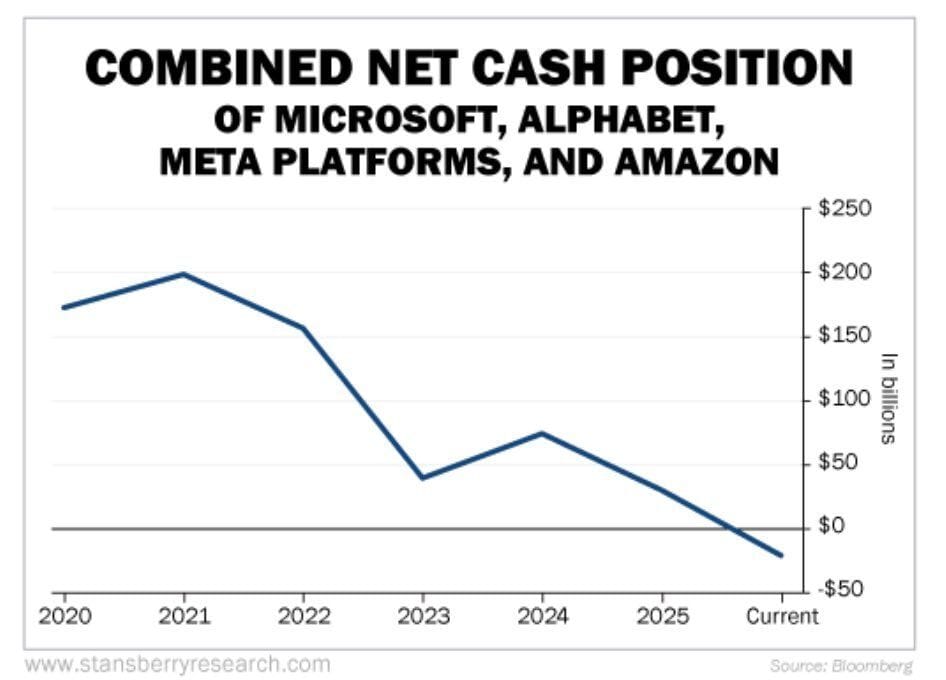

Sep. 7, 2025: The cash position of the Big 5 is now below zero as they continue to pour money into AI datacenters. AI capex is burning, free cash flow hasn't caught up.

Updates:

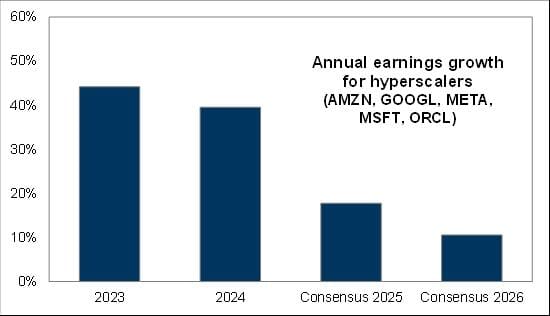

Momentum in annual earnings growth for hyperscalers is set to wane from here. (Goldman Sachs)

It’s clear there is a lot of hype:Web searches for AI are ten times as high as they ever were for crypto. S&P 500 companies mentioned AI more than 3,300 times in their earnings calls this past quarter. https://substack.com/@breakingnasdaq/note/c-153080469

"Today, I watch in awe (stupefaction really), as companies continue to throw endless resources at AI, I remember back to the Dot Com bubble and Global Crossing—fiber was the datacenter of that cycle, and Corning was the NVIDIA of its day (it lost 97% of its share price in the two years after it peaked)." https://substack.com/@breakingnasdaq/note/c-153083422

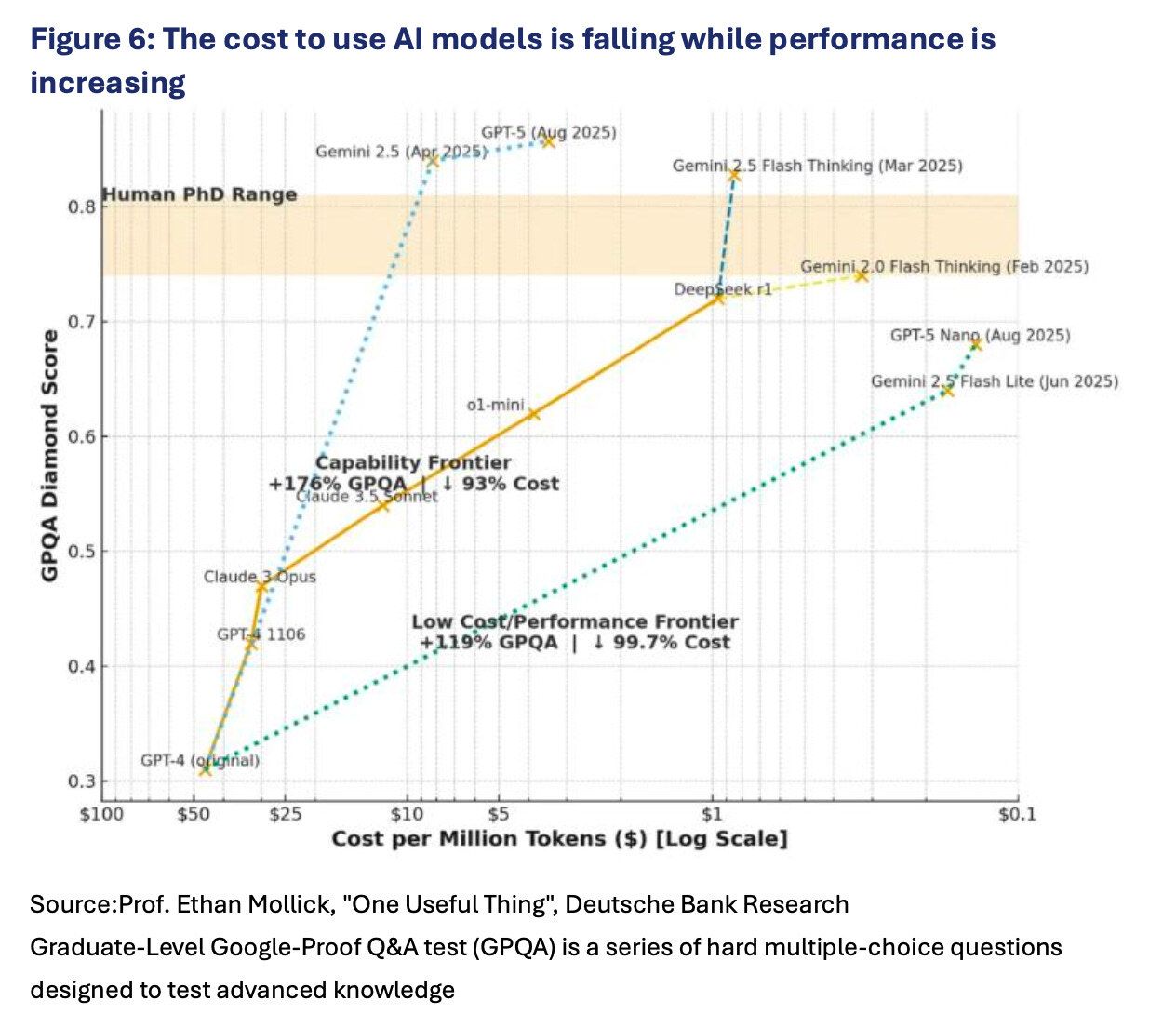

The cost to use AI models vs performance:

The cash position of the Big 5 is now below zero as they continue to pour money into AI datacenters. AI capex is burning, free cash flow hasn't caught up.

"The AI market right now is a recursive FOMO machine: a promising but unproven AI startup does a Series A that creates VC FOMO and leads to an immediate Series B in the same startup, which creates FOMO and leads to a Series A in a competitor that creates FOMO and leads to an immediate Series B in that competitor."

OpenAI set to start mass production of its own AI chips with Broadcom.

It feels very familiar:

Cisco created the hardware used to power the internet. This was essentially the Nvidia of the internet era, and it briefly became the world’s largest company at just over US$500billion - equivalent to 5% of US GDP at the time, prior to the bubble’s collapse. Nvidia is currently valued at 15% of GDP. The core belief then was that internet traffic would double every 100 days, thus requiring massive purchases from Cisco.

According to a research report published within weeks of the peak: “Cisco continues to argue that the industry will grow at 30-50% in countries with healthy economies. It sees several years of strong growth powered by a growing acceptance of the internet as a crucial tool for business and government…Revenues of $4.35 billion rose 53% over the year-prior number of $2.85 billion: FQ2 marked the eighth quarter of accelerating topline growth.”

Cisco’s business was booming, hence why it was viewed as a must-own name, similar to Nvidia today.

Alternative angles: https://open.substack.com/pub/breakingnasdaq/p/us-stock-market-its-a-final-countdown

A typical web search uses an average of 0.0003 kilowatt hours. An AI-powered chatbot query consumes between 0.001-0.01 kilowatt hours, depending upon the complexity. This is 3.3x-33.33x the electric power consumption of a traditional web search.

The AI market right now is a recursive FOMO machine: a promising but unproven AI startup does a Series A that creates VC FOMO and leads to an immediate Series B in the same startup, which creates FOMO and leads to a Series A in a competitor that creates FOMO and leads to an immediate Series B in that competitor. https://x.com/mattturck/status/1964068965115666734

Analysts predict that between February 2024 and February 2026 Nvidia will have sold some 6m Blackwells and 5.5m GBS. Assume that half of these end up in America, in line with its home market’s historical revenue share. If installed and operated at capacity, those chips would raise American power demand by 25 gigawatts. That is almost twice as much as all of America’s utility-scale producers added in 2022 and not far off the 27GW they managed in 2023. And that is not counting next-generation Rubin chips Nvidia plans to launch next year, or AI racks sold by rivals such as AMD, not to mention other power sinks such as electric cars. Between 2022, when ChatGPT ignited the AI boom, and the 12 months to June this year, the combined capital spending of America’s 50 biggest listed electricity providers rose by 30%, to $188bn - a compound annual increase of 7%, adjusting for inflation. According to S&P Global, a data provider, they are planning to add new plants with a collective capacity of 123GW, on top of the 565GW currently in operation. Bernstein estimates a potential power shortfall in America of 17GW by 2030 if the chips get more energy efficient, and 62GW if they don’t. Morgan Stanley puts the gap at 45GW by 2028.

Source: Economist, https://substack.com/profile/170771739-breaking-nasdaq/note/c-152618676

Report: NVIDIA agreed this summer to rent 10,000 of its own AI chips from the cloud firm, Lambda, for $1.3 billion over four years. https://substack.com/profile/170771739-breaking-nasdaq/note/c-152615727

"Last night, NVDA CEO Jensen Huang predicted that AI capex will soon hit $1 trillion per year. Why? That's the pace needed to justify NVDA's $4.5 trillion market cap, and keep the AI bubble inflated. One minor problem... the total revenue across the major AI players (OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, etc.) is running at less than $20 billion annualized. Never mind the fact that these companies are burning tens of billions in cash to generate this revenue. Meanwhile, 95% of enterprise AI projects fail to deliver any revenue uplift. We're looking at one of the greatest episodes of capital misallocation in history." https://x.com/Ross__Hendricks/status/1961024148378877969

At the height of the dot-com boom, American Metrocomm Corp., a Louisiana phone carrier burning cash, was already interviewing bankruptcy lawyers. “There was no rhyme or reason that anyone in their right mind would loan them any money,” recalled Michael Henry, who later became Metrocomm’s chief executive.

But Cisco Systems Inc. was happy to oblige. The Silicon Valley networking giant extended more than $62 million in credit to Metrocomm, a lifeline that quickly translated into new sales of Cisco routers and switches.

Metrocomm wasn’t alone. Over the late 1990s, Cisco poured billions into shaky telecom firms through its financing arm, Cisco Capital. The loans weren’t gifts; they were a sales machine. Often the “credit” came in the form of Cisco gear itself, booked as revenue even before customers had made a single payment. By 2000, executives said such financing and leasing deals accounted for roughly 10% of Cisco’s $20 billion in annual revenue.

The strategy worked wonders while the bubble inflated. But as the telecom bust arrived, the risks became harder to ignore. In 2001, Cisco acknowledged that many of its customers were unlikely to repay and set aside nearly $900 million for bad loans.

One of those customers was Rhythms NetConnections, an Englewood, Colo., internet provider founded by a major Cisco shareholder. Rhythms was bleeding money from the start, losing $36 million on just $1 million in sales in 1998. Its IPO prospectus warned of years of red ink, and S&P rated its debt deep in junk territory. Still, Cisco shipped Rhythms $20 million in gear on credit just before the IPO in 1999 and kept financing it even as the stock collapsed. By the time Rhythms filed for bankruptcy in 2001, it owed Cisco more than $30 million.

HarvardNet, a Boston-based broadband provider, told a similar story. With less than $5 million in sales and a negative net worth by the late 1990s, it compared Cisco gear to rival Paradyne’s and concluded Paradyne’s technology was superior. But Cisco went straight to the top, offering as much as $120 million in credit, on terms that allowed deferred payments and even spending on non-Cisco equipment. HarvardNet’s leadership took the deal, and Cisco became its dominant supplier.

By early 2001, internal documents showed, Cisco had racked up financed-lease exposure of $1.3 billion across 735 customers, including $233 million tied to high-risk borrowers. What once looked like a clever growth hack had become a costly reminder that lending to struggling customers is no substitute for sustainable demand.

Source: Kakashiii111, https://x.com/kakashiii111/status/1970551588289945924?s=46

Goldman's head of Delta One slams Nvidia's increasingly grotesque vendor financing circle jerk:

"... definitely not old enough to have been around trading during the tech bubble and let’s level set, multiples are now where near that point in time. That said, vendor financing was a feature of that era and when when the telecom equipment makers (Cisco, Lucent, Nortel, etc.) extended loans, equity investments, or credit guarantees to their customers who then used the cash/credit to buy back the equipment…well suffice it to say, it did not end well for anyone." - Rich Privorotsky

Now replace all “Internet” with “AI”. Boom.

Sources:

“Bigger fools. The nature of bubbles, however, is that no one can tell when they’ll pop. If the Nasdaq was overvalued in 2000, it was also overvalued in 1999 and 1998 and 1997. Investors rushed to buy stocks in the late 1990s so they would not miss out on the profits that their friends were making. The buyers, many of them overloading their portfolios with big-cap tech stocks, firmly believed they could sell to some greater fool who would always pay more than they did.”

Dejavu:

NVIDIA's Capex in context of Cisco and IBM:

Hundreds of billions of dollars are being “thrown” around in AI:

The hundreds of billions pouring into AI infrastructure are creating a sugar high for related stocks and the broader indices. But it raises a critical question: what is the ROI on a $500 billion data center?

Artificial intelligence is being built on the cheapest labor the digital economy can find. While investors pour hundreds of billions into AI startups and infrastructure, the people training these systems: reading, correcting, and rating machine output, earn barely above minimum wage. The result is a paradox: a trillion-dollar industry powered by underpaid workers whose fatigue and low morale quietly shape the quality of the models themselves. This hidden layer of “cheap intelligence” may soon become the sector’s most expensive problem.

Microsoft just revealed that OpenAI lost more than $11.5B last quarter:

"We have an investment in OpenAI Global, LLC (“OpenAI”) and have made total funding commitments of $13 billion, of which $11.6 billion has been funded as of September 30, 2025. The investment is accounted for under the equity method of accounting, with our share of OpenAI’s income or loss recognized in other income (expense), net."